They lacked a symbol to serve the function of radix point, so the place of the units had to be inferred from context : could have represented 23 or 23×60 or 23×60×60 or 23/60, etc.

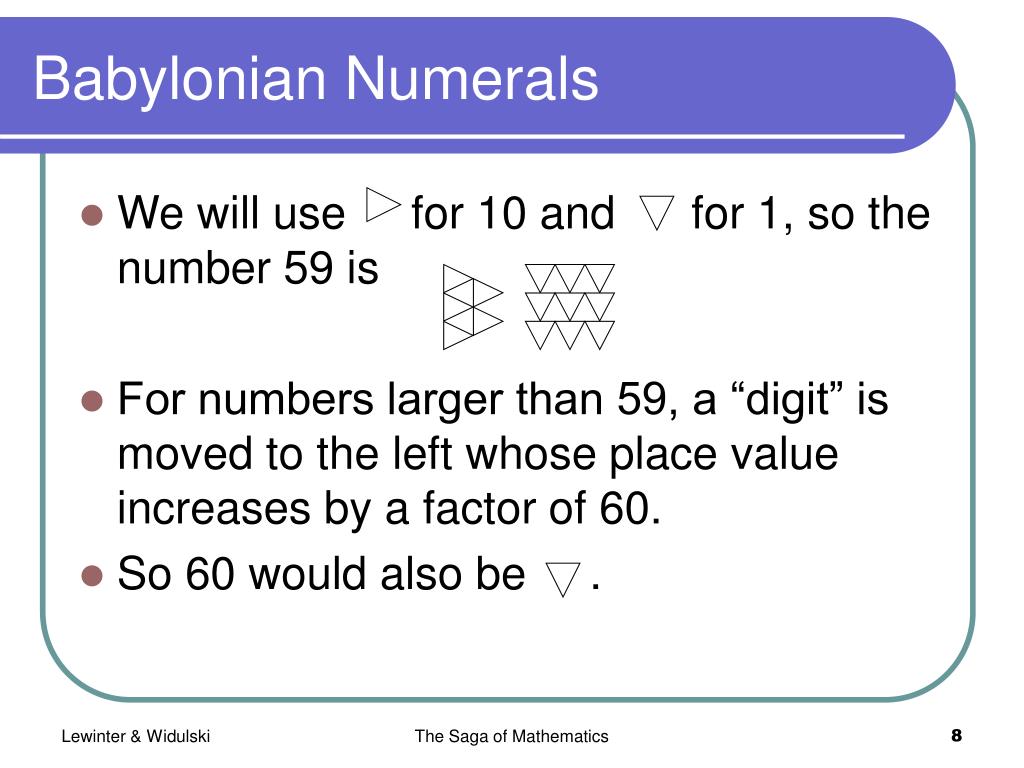

Babylonians later devised a sign to represent this empty place. A space was left to indicate a place without value, similar to the modern-day zero. These symbols and their values were combined to form a digit in a sign-value notation quite similar to that of Roman numerals for example, the combination represented the digit for 23 (see table of digits above). Table of Reciprocals).Only two symbols ( to count units and to count tens) were used to notate the 59 non-zero digits. For this they used a table of reciprocals (see The last example, can be written as the division problem, The multiplier, and place the sexagesimal point 3 places from In this case there are 3, one in the multiplicand and 2 in Finally, count the number of sexagesimal places, Next, we add the columns, remembering to carry when Since 1 times anything is the anything, the next row is easy

Using the babylonian numerals. plus#

Next 20 × 10 is 200 plus theġ0 we carried is 210 which is (3,30) 60, so you put theģ0 down and carry the 3 which just comes down. Plus the 13 we carried is 613 which is (10,13) 60, so you × (0 1, 20) using a method similar to what we do today. Let's consider the following: Example: Muliplty (10, 30 40) 60 When a product is greater than 60, you carry to the next place. The Babylonians could also have multiplied the way we do today, since they used a place value system with 60 as the base. Remember that multiplication is commutative, x × y = y × x, so the order doesn't matter and x can always be the larger number. When using the second formula, it is important to make x the larger number so you avoid negative numbers. Let's look at an example using the second formula. Let's look at an example using the first formula. If all the 'digits' in a base-60 number are divisible byĢ or 4 then so is the number itself and the result is obtained by simply dividing each digit by the divisor. The first isīoth formulas involve division which the Babylonians would haveĭone by multiplying by the reciprocal, which we will look at in a There are two formulas that can be used to find a product of two numbers using squares. The table at the right shows the squares of the numbers from 1 to Let's take a look at how they would have used a tablet containing the squares of numbers. Look at one more example: Example: Muliplty 23 × 49 using a

Now, we simply add these two base-60 numbers to get the result ofĪmazing, the multiplication problem becomes a problem of addition!īut, this makes sense since multiplication is repeated addition. Using the table of muliptles at the right, we see that Now, to multiply 23 × 57, we write 57 as the sum 50 + 7 and use the distributive law to obtainĢ3 × 57 = 23 × (50 + 7) = 23 × 50 + 23 × 7 Remember,īabylonains used base-60, so the table contains (1,9) 60 for A Babylonian studentĬould have used a tablet containing the multiples of 23. How they would have used a table of multiples. Reciprocals to perform the operation of multiplication. The Babylonians used tablets containing multiples, squares, and Babylonian Multiplication The Saga of Mathematics: A Brief History by M.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)